“Donora Death Fog”: A Small Western PA Town’s Crisis, that Gave Birth to the Environmental Movement

by Michael Machosky

January 16, 2023

Western Pennsylvania has given rise to so much of the environmental movement — simply by being so catastrophically polluted by industry. And one small town in Washington, Pa., Donora, paid the steepest price.

In 1948 — just before the annual Halloween parade and a hotly-anticipated high school football game against rivals Monongahela — a thick yellowish fog descended on the city. When it cleared several days later, 20 people were dead and thousands were sickened.

As killer smogs go, it wasn’t the worst. That would be Belgium in 1930, or London in 1952, which may have killed as many as 12,000. But it was a wakeup call for America, and one that spurred action. If there was a single, catalyzing event sparking the creation of the American environmental movement, this might have been it (Pittsburger Rachel Carson’s landmark book “Silent Spring” was another).

Author Andy McPhee’s new book, “Donora Death Fog: Clean Air and the Tragedy of an American Mill Town” (University of Pittsburgh Press), tells this story in vivid detail, while putting it in context. The overwhelming industrial power that had recently drowned the Axis powers with a rain of steel came with a terrible cost.

McPhee, an author with a long career publishing stories for children and young adults, was looking for an environmental story to tell, when one jumped out at him from a most unexpected angle. He was watching Netflix’s “The Queen” with his wife, specifically the part when The Great Smog trapped London in its grip.

One of the investigators said to (Prime Minister) Clement Attlee, “Does the name ‘Donora’ mean anything to you?’”

It didn’t mean anything to McPhee, who lives in Eastern PA. But he looked it up, and found the story of Donora’s infamous fog (before the word “smog” was common).

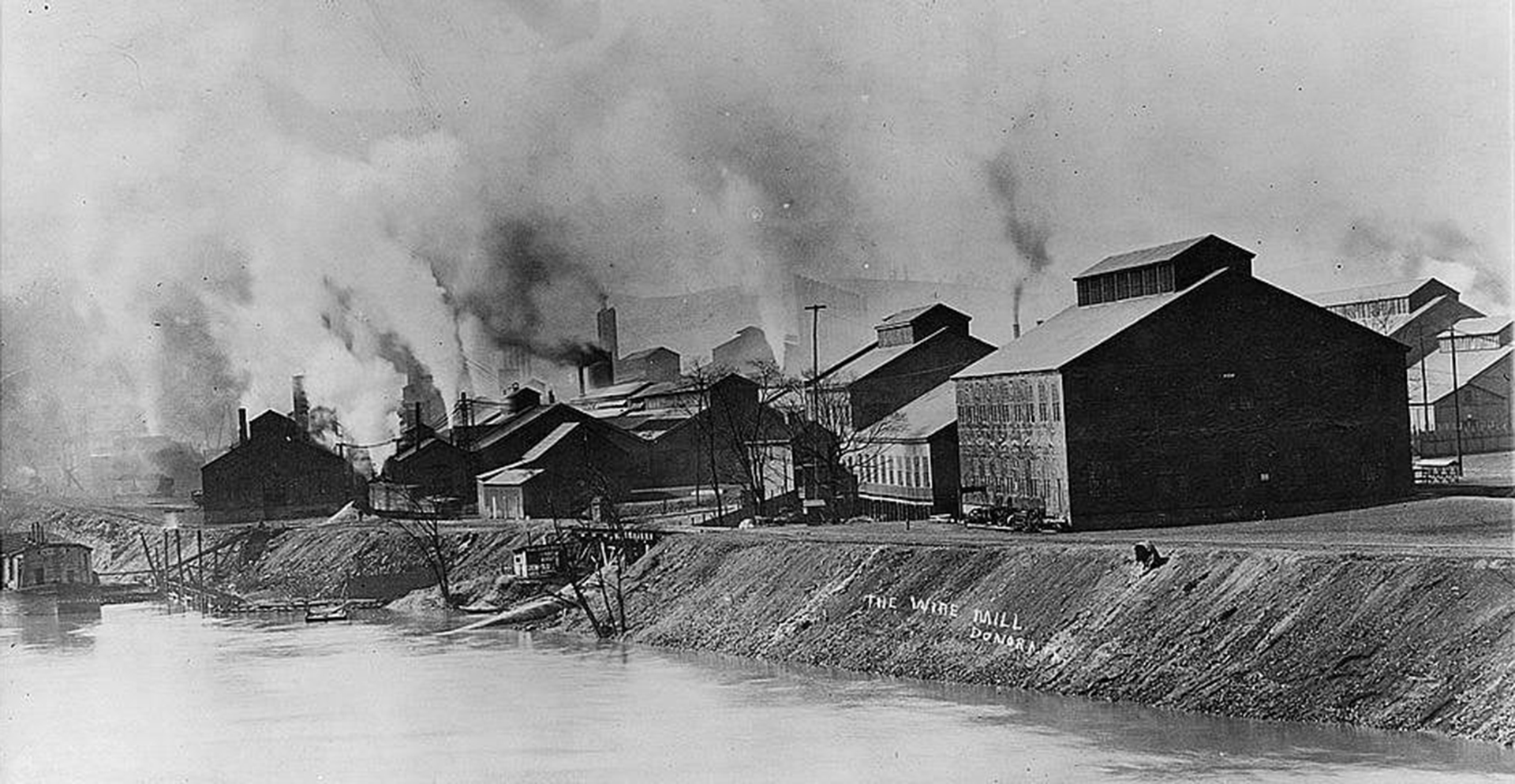

What happened to Donora was called a temperature inversion, a not-that-uncommon meteorological occurrence when warmer air is held above cooler air, which traps pollutants below. A fog settled over Donora trapped all the emissions from the zinc and steel mills, turning the town into a kettle of industrial pollutants, with the lid firmly but invisibly shut. (Temperature inversions still happen regularly in the Mon Valley).

The story of the Donora Fog didn’t disappear from view afterwards. It was a big story. But people in Donora understandably didn’t want it to become their town’s defining characteristic, and there was plenty of incentive to downplay it.

“For a number of years afterwards. I believe that U.S. Steel (owner of most of the polluting factories), behind the scenes, squelched whatever stories they could, and they put such a spin on it,” says McPhee. “Even to this day, some people in town still believe now that it had nothing to do with the mills.”

The timing was right for change, however. The desperate production-at-all-costs mentality of the war years was over.

“President Harry Truman was elected in November,” says McPhee. “And one of the core issues that landed on his plate early in his presidency was Donora. Now, granted, it took several years, but that's our government. And he created the first conference on impact on air pollution. Eventually, that brought about the Air Pollution Control Act of 1955.”

“Donora Death Fog” puts the story in context, showing how the town of Donora was founded by industrialist William Donner, and how it became one of the fastest-growing places in the world in the early 20th century. People came from all over the world to work in the mills. It was in many ways a town on the cutting-edge of industry. Thomas Edison even designed fireproof concrete housing for workers, the neighborhood now known as “Cement City.”

McPhee goes into great detail about work in the mills, and the extreme conditions of heat and poisonous air inside. It’s quite sobering that these were considered good jobs, worth leaving home and family for, in many cases. (My dad worked in a steel mill scraping carbon off the inside of a furnace one summer. His father was a blacksmith for Heinz. This is the first book that I’ve read that really seemed to explain exactly what it was like).

“I was stunned at the amount of toxins that were in the air,” says McPhee. “Thousands of tons of toxins spewed out of those smokestacks every day: sulfur dioxide, sulfur trioxide, zinc oxide, all kinds of stuff.”

Initially, Donora didn’t react to the fog. Focus was on the big football game against rivals Monongahela. But when the fog didn’t lift, people realized something was wrong. It didn’t truly sink in for many until syndicated national radio host Walter Winchell mentioned people dying in Donora on his show.

McPhee tells the stories of the local doctors who tried to get the vulnerable out of town, and the townspeople who raised the alarm, many of them heroically.

Some lessons were learned. Some were known already and ignored.

“They had smokestacks 110 feet high when the ceiling inversion layer was like 320 feet high,” notes McPhee. “So the smokestacks were not even close to throwing emissions above the inversion layer. And yet, there were steel mills throughout country that had increased their stack size to over 300 feet specifically to get it above typical inversion layers. So not even the (steel) industry listened to itself. I think that's probably the biggest lesson for me — when the people who know tell you something's wrong, and you need to do something about it, you’d better listen.”

Leave A Comment