THE GREEN VOICE VOYAGER

A Conversation with Mary Tremonte: Talking art, queer ecology, and our connection to the more-than-human world

by Emma Honcharski

June 3, 2024

This month, I sat down with Pittsburgh-based artist, DJ, and educator Mary Tremonte to share a bit about her work. Mary’s printed work bridges connections between the more-than-human and the human world, depicting playful and connected relationships of fungi, plants and animals. You can find Mary Mack Prints’ work at the Fallingwater gift shop, at art and craft fairs around the region (including the upcoming Queer Craft Market), through Justseeds and her personal website.

Locally, she has also worked with Shiftworks (formerly Office of Public Art), as part of the Environment, Health, and Public Art Initiative. In coordination with Grow Pittsburgh, Tremonte created a project about soil pollution and remediation called Dirt is Beautiful, which involved silkscreen printing with soil. It involved getting in depth with community gardeners about history of place and what is going on in the dirt under our feet. The project also included interviewing folks from organizations that work with soil in different ways such as Worm Return, a community composting service, and Women for a Healthy Environment, to talk about lead contamination in schools and public spaces.

Tremonte is also a member of Justseeds Artists’ Cooperative, a decentralized group of 39 artists and printmakers who make graphic work in tandem with movements for social and environmental justice. Tremonte runs Justseeds’ Pittsburgh-based online store. The group creates graphics that people can download for free as part of social movement work, in addition to creating thematic print portfolios with a range of organizations that can be used for fundraising. Recently, Justseeds worked on a project with the Center for Biological Diversity about endangered and extinct species, and the humans that are working to protect those species.

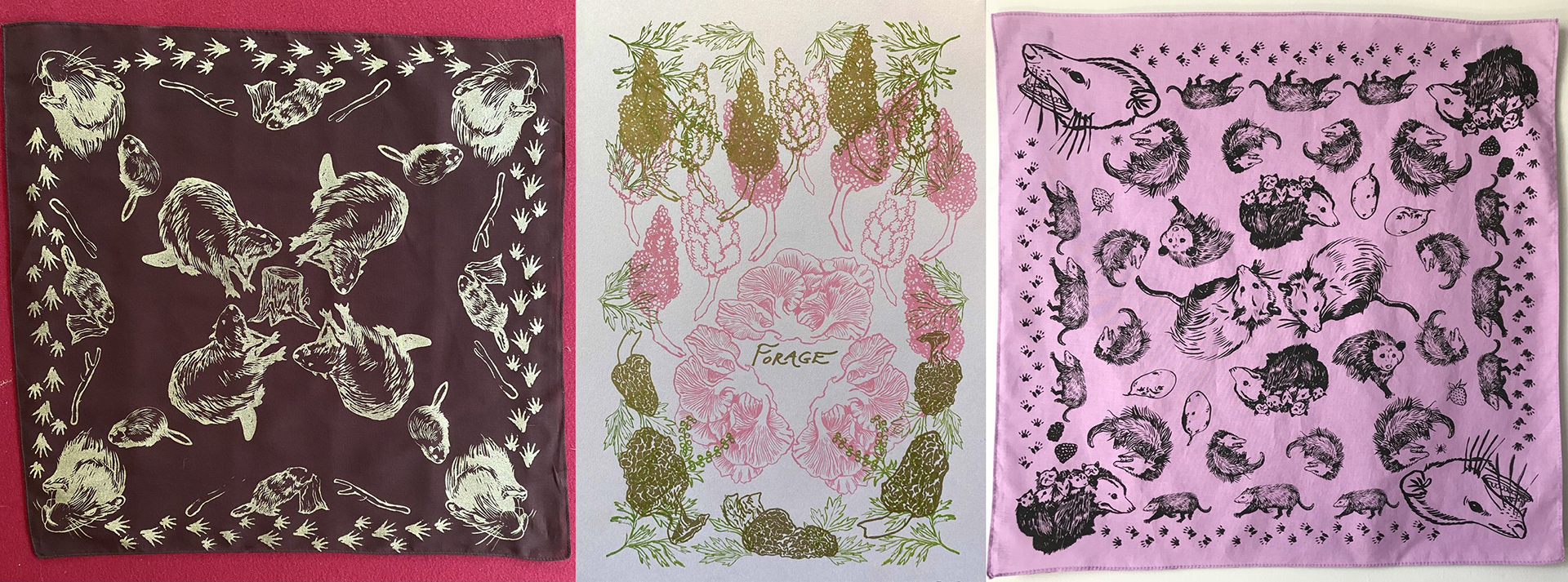

In addition, she co-organizes Queer Ecology Hanky Project with artist Vee Adams, an ongoing exhibition of over 130 artist-made bandanas on the theme of queer ecology. The exhibition has been shown at White Page Gallery in Minneapolis, MN; Irma Freeman Center for Imagination in Pittsburgh, PA; Maine College of Art in Portland, ME; Women’s Studio Workshop in Rosendale, NY; and Zygote Press in Cleveland, OH. In June, the exhibition will open at the Plains Art Museum in Fargo, North Dakota, where it will be on exhibit through the end of the year, with special programming in August for Fargo-Moorhead Pride. In early 2025, it will show at Snap Gallery in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

EH: Can you tell me a little bit about you and your work?

MT: My name is Mary Tremonte, I use she/they pronouns, I have lived in Pittsburgh, on and off, for the past 25 years. I would describe myself as an artist, DJ, printmaker, educator, organizer. The main form my work takes is silkscreen printing and, also, I DJ and organize events and workshops. I would say that connection is at the root of everything I do, so creating objects and experiences that can bring people together to find one another. Some of the forms that takes can be a publication, like a zine, or an exhibition, as a way to create publics around an idea.

EH: You have written that your work aims to “create temporary utopias and sustainable commons through pedagogy, collaboration, visual pleasure, and serious fun.” How does this come through with the prints, hankies, stationary, patches that you make that are ecology- and nature- forward?

MT: I think about ways that the more-than-human world communicates with one another non-verbally — through color and movement, and also thinking about how humans communicate with one another non-verbally, in the clothing that we wear and the different signifiers we wear to kind of show our affinity, show what we're into. I was a teenager in the 90s and was really into DIY punk and zines, and you know how you would literally wear your politics on your sleeve with a screen printed patch of a band you liked or a button expressing a political idea. I think about that as a lexicon, as an alphabet of communication, and thinking about symbols of communication. That also intertwines with my practice of throwing community-based dance parties, and thinking about ways to commemorate these kind of ephemeral, temporal spaces of the dance party.

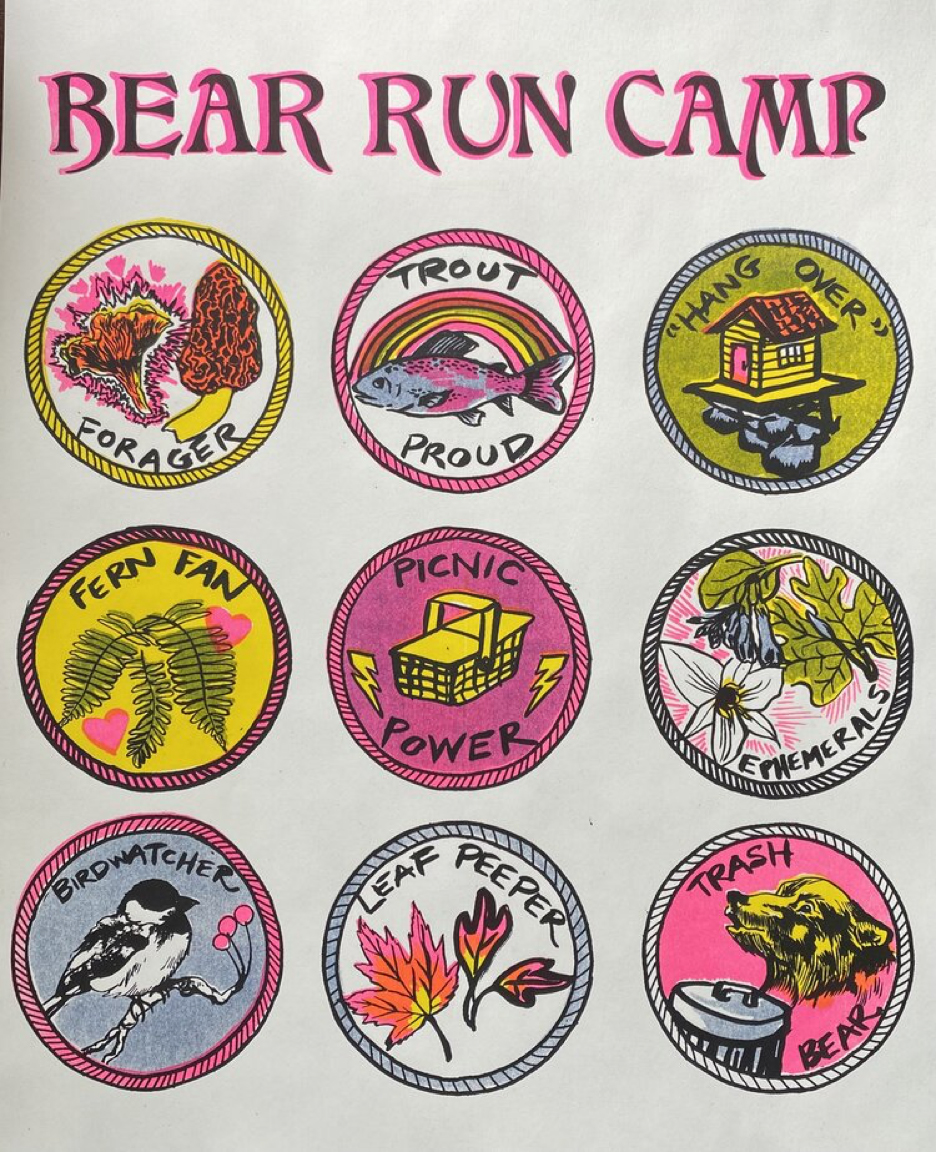

I co-organized a monthly queer party called Operation Sappho for six years, and we'd have a theme each month, and one month our theme was queer scouts. So people wore their old scout uniforms, people who identify as queer now, but might not have when they were younger perhaps, you know, being in a homosocial, context of scouting where they had some of their first queer feelings and experiences. Anyway, that was the theme of the party. I hand drew and screen printed these really simple queer scout badges, thinking about, if there was a Queer Scouts, what would be the badges that you would earn?, and then giving those out to participants at the party. And then after that, I was like, well, I should make the poster of all the badges that you'd want to earn as a queer scout.

I remember my own Girl Scout-hood and looking at that poster and thinking, oh, I really want that badge. I want that — there is no foraging badge — but I want that foraging badge. So I made the poster and my friend said, well, you should actually make embroidered badges. So I started making embroidered badges of those queer scout badges, which the main one that says queer scouts, it's a three fingered salute and some lightning bolts. And I've made and remade that badge dozens of times. Last count, there's over 8,000 of them out in the world. I've seen people bootleg it, I've been collecting images of it just via social media, via Instagram. But I've seen people draw it onto ceramics or embroider it themselves, or someone even got it tattooed on their body.

So to me, that speaks to the root of doing that and being part of punk culture and thinking about symbols that communicate our ideas and what we're into. And now this image of the queer scouts has this life, as a symbol, outside of me as an artist.

And then also thinking about gay hanky code, that started with like gay cis men leather culture in San Francisco in the 70s. Kind of tongue in cheek, but a way to non-verbally communicate what kind of activities you're into — riffing on that, but queers have been updating the hanky code for decades now, for other bodies and other activities and identities, and in a really playful way.

Further riffing on that, I did a project with Fallingwater, as part of the Fallingwater + PG&H Maker Project in 2021. We made prototypes for their gift shop to carry, and I really honed in on the land that Fallingwater is on, which is Bear Run Nature Reserve. When the Kaufmanns first bought that land, they operated a summer camp for their employees, so thinking about Bear Run Camp, I made this poster of badges, about what are the different activities you do when you’re on the land that Fallingwater sits? There’s a birdwatching badge, a forager badge, a spring ephemerals badge, a picnic power badge.

EH: Can you tell me a little bit about the Queer Ecology Hanky Project?

MT: The Queer Ecology Hanky Project is an ongoing exhibition of over 130 artist-made bandanas on the theme of queer ecology, which is an emergent field of study that looks at both ecology — which is not just individual species but how species interact with one another, their relationships — and then also queer theory, so looking at ecology through a queer lens, not through a heteronormative and capitalist lens. So, looking at different kinds of observed behavior of mammals and birds and mycelium and plants. Through a traditional, western, Darwinian lens you might view certain kinds of behavior as competition, but actually, there's ways that animals communicate and engage in homosexual activities that are for pleasure, and not for competition. Also, there’s just a lot that we can learn from the more-than-human world, of ways to work together, through mutual aid and reciprocity.

Artist Vee Adams and I did an open call for artists in 2019, and asked artists to submit an idea for a bandana, and then to do an edition of 20 to 30 of the bandanas.

Thinking about my work in ecology, I think about the more-than-human world, non-human species — what we might think of as ecology or the environment, but also the ecologies of humans, especially of queer humans and how we create systems to be with one another and support one another.

EH: How do you think about both social and environmental justice, and sustainability in your work as both an artist and educator?

MT: I try to think about everyone, and also think about who's not in the room when organizing or coordinating an event. I think that's rooted in social justice and environmental justice because most of the people who are feeling the brunt of destruction of the environment are poor people, people of color, racialized people. Wealthier white people generally don't have to live near the power plant or the fracking site, or can afford to not be there.

Miriame Kaba says that hope is a discipline. I think of sustainability, kind of like that, hope as a discipline and a practice, and something that we do, but that we never fully arrive at, it’s like a utopian horizon. To paraphrase what José Esteban Muñoz has said, queerness is the utopia which means nowhere, so we’re always reaching for it, but never arriving at it, but it’s the reaching for it that is the queerness and utopian space. [...]

I think it’s really easy these days to feel demoralized with the state of so many things in the world, but to keep going and to not give up, to keep having some hope for the future and acting in a way that belies that. Today, before we met, I was at my community garden plot planting my starts and picking strawberries and looking at how the garlic is doing — gardening is a form of sustainability and also of hope. This community garden plot is a form of belief that you will make things grow and then you will eat them.

Leave A Comment